From the Couch to 1 mile or 1 kilometre

by Greg Dea and Mitch Rowe

The desire to take up running is a good one. Honour it. There is a lot of information about how to run your first three miles or five kilometres (km), but often getting to the first mile or kilometre mark is the inertia that needs overcoming.

There’s a gap in practical wisdom for progressing from not running to running one mile. Three miles is 4.8 km, so a 5 km run is effectively a three-mile run. We give you the metric equivalent because the “couch to 5 km” library of programs is full, but the success often depends more on being able to get going efficiently and safely up to 1 km, rather than continuing up to 5 km. By extrapolation, the success often depends more on being able to get going efficiently and safely up to one mile, rather than continuing up to three miles.

This early journey matters greatly for anyone beginning running or returning to running after injury. There are future livelihoods at stake when it comes to getting into shape – think about those civilians aiming to pass physical fitness tests for tactical professions like firefighting, police, emergency services and military. Some are given generic pre-enlistment fitness programs, like this one, to bring them up to a running capacity for testing.

What is different about this program is where it starts.

This program expects that the client isn’t currently running. Many of the currently available running programs are designed around tests that require a minimum of 1 km or 1 mile running tolerance – the maximum aerobic speed test (MAS), the YoYo endurance tests, the Shuttle Run tests, and others. But where does someone start when they don’t fit that criteria of being able to run 1 mile or 1 km? Right here is where they start.

That’s “the why” of this program, because there’s a gap in knowledge and experience being passed on for the first 1 mile or 1 km of running.

Each coach or therapist will have their own bias toward tolerance levels for what is considered success in a program such as this, and we would recommend a simple cut-point be that the individual can run continuously for 1 mile or 1 km. We have suggested that if the individual has had to start again, or start from not running, they would most likely finish this program running 1 mile in 8 to 11 minutes or 1 km in 5 to 7 minutes, even though we’ve given no suggestions during the program about speed or other measures of intensity. If an individual cannot run quicker than 11 minutes for the mile or 7 minutes for the km, it is likely there would be several risk factors present at pre-program screening that would contribute to this.

Further, each coach or therapist will have their own bias towards tolerance levels for what is considered efficient or safe for a program such as this. Our own bias is to be guided by a multi-factorial approach to identifying risk factors for future injury – our bandwidth or tolerance level is guided by strong research and wise practice.

A recent study highlights that the more risk factors a person has, the more at risk they are for future injury – in a mixed military population [1]. Since the population consisted of individuals in a wide variety of roles in the military, include a variety of combat support services, it is close to a general population. To that end, prior to starting a training program, we screen individuals using many elements that are also found in this study, with appropriate intervention afterward that have been shown to lower risk, either in group correctives, individual correctives, on individual treatment plus correctives [2, 3].

We would also be implementing, where possible, desirable and practicable, non-running physical preparation training in addition to this program. Where not desired by the client, possible or practicable, this program in isolation works well.

Now for the what and how – the program – concisely.

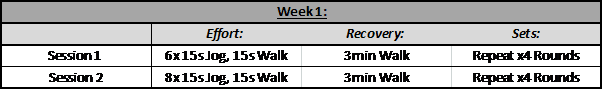

First, the “Couch to 1 mile” program:

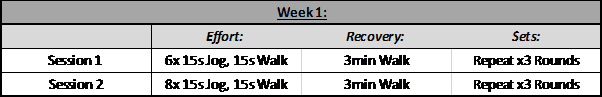

Now, the “Couch to 1 km” program:

Mitch and I have often considered a pre-program. Is it needed? The answer is, “it depends.” It depends on what you found in your screening. Each coach uses their own critical thinking to decide whether the week 1 load is doable. There are some clients who aren’t ready for straight ahead jogging, so if you are looking for a tried and tested program to bring a client up to week 1, try “phase 1,” directly extracted from my book, Return to Field Sports Running Manual.

Take a look at phase 1 for a pre-program.

Phase 1 is full of lateral movement drills, that is to say, a form of exercises that require you to move sideways. There are good reasons for this:

- Lateral movement drills challenge your tendons, bones, muscles, joints and nervous system in a safer way than simply beginning to run forwards;

- Lateral movement drills test your cardiovascular system in a gentle introductory way;

- Lateral movement drills will also, very quickly, demonstrate how close you are to progressing to straight line running.

Phase 1

Low to high intensity lateral movements

Drill 1: Side stepping, from walking pace to skipping – you choose the speed. There are three speed options:

- slow (simply side-stepping)

- medium (side stepping quickly or side-skipping slowly)

- high (side skipping at a fast pace).

A search on YouTube for side stepping drills will reveal many options, but my preferred drill for this running program is described very well by Aaron King Sports Training in this YouTube video:

A ladder is NOT required.

Choose a distance that is convenient, but between 10 to 30 metres is what I’ve used mostly, before changing direction. Keep moving back and forth within that chosen distance for 1 minute. Rest for 30 seconds. Repeat 3 times. This is written as:

3 x [(1 minute over 10-30m) / 30s]

Drill 2: Crossover stepping. This is also known as a carioca, or a grapevine.

You will move laterally while stepping one foot in front of and across the other, then alternating that with a step behind and across the other. A simple search on YouTube will reveal several videos, and again, I’m a fan of Aaron King Sports Training’s video:

As for drill 1, a ladder is NOT required.

For example, if you are moving laterally to the right:

• Begin in what is known as the base position—feet approximately shoulder width apart with a slight bend at the knees and hips—as if you are preparing yourself for a sudden command to commence;

• Step first with your left foot, across the front of the right foot;

• Next, step to the right with your right foot (you should be in base position again);

• Then, step with your left foot, to the right, behind and across the back of the right foot;

• And, step again with the right foot, to the right, to return to base position.

• Repeat this alternating crossover pattern, one-in-front, one-behind, for the prescribed distance and time.

• The dosage is 3 x [(1 minute over 10-30m) / 30s]

You may progress from a walking pace to high speed.

Drill 3: In and out agility drill.

In this drill, you will need the same distance – 10m to 30m – preferably with a line drawn on the ground to guide. You will move laterally to the right in this example. Before I explain, consider that this drill is often known as an in-in-out-out drill. A quick search for “in & out agility drill” or “in in out out” in YouTube will usually yield some examples such as these by iTrain Hockey and Aaron King Sports Training at:

1: iTrain Hockey

2: Aaron King

You won’t need an agility ladder as in the two videos linked. A field line is all that’s required.

• Start in a base position, behind the line.

• Step over with the right foot first, then left, then step back over the line with right, then left.

• Continue this four-step while moving laterally.

• The dosage is 3 x [(1 minute over 10-30m) / 30s]

A similar drill is known as the icky shuffle, and a search on YouTube will reveal plenty. After your injury, these variations are the first re-introduction to pushing off to jog in a forward direction. It is also the first re-introduction to decelerating. Perform 3 repetitions, each for 1 minute with 30 seconds rest in between.

In the early phase, the above three drills can be done at a walking pace. They can even be done in an aquatic environment to reduce load on the body.

These three drills progress from pure lateral movements (drill 1) to lateral with rotational movements (drill 2) to lateral with linear acceleration and deceleration movements (drill 3).

If you don’t tolerate forward and backward movements yet, you should limit participation to the first two drills—lateral and carioca/grapevine.

If you don’t tolerate rotational movements initially, you should limit participation to the lateral movements and forward/backward movements.

If you don’t tolerate lateral movements, you should limit participation to forward backward and carioca/grapevine in place, without the lateral movement.

Typically, everyone can laterally step at a walking pace when they aren’t injured or suffering a neurological condition, in which case all three of these drills can be done at least at a walking pace.

Stay in phase 1 and DO NOT PROGRESS to the next phase if the following occurs:

- There is a reaction on the following day (i.e. soreness, tightness or guarding)

- There is a noticeable change of walking pattern

- There is a need to decrease speed to maintain pain-free technique

- Another condition presents itself that requires assessment before continuing.

What’s next?

Next, proceed to their follow-up artice, Beyond the 1km: Using a three-speed approach to get to 5km.

And check out Greg’s book, Return to Field-Sports Running Manual, available in ebook format and paperback.

- Teyhen, D.S., et al., Identification of Risk Factors Prospectively Associated With Musculoskeletal Injury in a Warrior Athlete Population. Sports Health, 2020: p. 1941738120902991.

- Huebner, B.J., et al., Can Injury Risk Category Be Changed in Athletes? An Analysis of an Injury Prevention System. Int J Sports Phys Ther, 2019. 14(1): p. 127-134.

- Schwartzkopf-Phifer, K., et al., THE EFFECT of ONE-ON-ONE INTERVENTION in ATHLETES with MULTIPLE RISK FACTORS for INJURY. Int J Sports Phys Ther, 2019. 14(3): p. 384-402.