Models of Periodization

This article is an excerpt from The System, Periodization for the Strength Coach by Johnny Parker, Al Miller, Rob Panariello and Jeremy Hall

Professor Yuri Verkhoshansky defined periodization as the “long-term cyclic structuring of training and practice to maximize performance to coincide with important competitions.”[i] In general terms, it is the system of program design that involves planned, systematic changes in these training variables—intensity, volume, frequency and exercise specificity. This is where we take all the components we can manipulate, determine the purpose of the training, and then structure a plan across a timeline to achieve that goal.

In terms of program design for athletics, the goals should always be to reduce an athlete’s injury risk and maximizing athletic performance. Those are nonnegotiable. It also means your training program should not only serve to strengthen your athletes to reduce injury on the field, it should also not create injury or dysfunction from the training itself.

Too often, the programs we encounter in the weightroom are so focused on maximizing strength or work output above all else, common sense goes out the window and the athletes are consistently overtrained and breaking down before they set foot on the field. In recent years, there have been an alarming number of athletes being injured—and in some cases dying—from workouts that look more like punishment than training to improve performance.

You can build a periodized plan around a specific training objective, such as increasing vertical jumping ability or bench press strength specifically in preparation for the NFL Combine. However, more often than not, our goal is to develop the qualities of strength, power and speed in service of a sport. There must be some level of proficiency of all components of performance, with different emphasis depending on the demands of each sport. Your program design should address all of those components to help your athletes, not hinder them.

There have been many books written on periodization for sports performance, some of which came from the coaches we spent time with in Eastern Europe and Russia. We are not looking to reinvent the wheel or retread the works of others. Today, the biggest distinctions to be made using the current concepts of periodization deal with linear, block and undulating periodization.

Linear Periodization

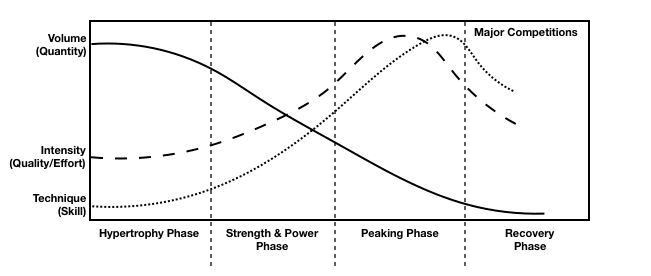

Linear periodization is considered the “traditional model” of program design, where there is a progressive change in volume and intensity across multiple cycles. The basic design is that volume will steadily decrease as intensity increases over generally longer training periods. In theory, this model provides concurrent development of strength and technical abilities in a gradually advancing manner—hence, linear. The training effect will be general, and moves from more of a hypertrophy phase to a strength phase, toward a power and speed emphasis during a peaking phase, and then a recovery phase.

The greatest issue with this model of program design is that the body does not adapt and progress in a linear fashion. A linear progression will often demonstrate good results for a novice athlete, as any type of strength training produces gains in size and strength in an untrained individual.

For a more advanced lifter, there may be steady progress made over six-to-eight weeks, and then we either see the athlete’s progress plateau or potentially even decline due to overtraining if the training intensity continues to steadily climb too long. On top of that, if you do not continue the reps-per-set protocols that are best for the quality you are trying to emphasize, you will lose the gains in that quality when you shift to emphasize another.

For an advanced or high-level athlete, linear periodization is particularly ineffective due in part to the much slower rate of physical adaptations in a trained individual. It also does not fit well in the competitive model for most sports.

For track or single event sports where there is a clear point in time to achieve peak performance, planning in a more linear fashion makes sense. The problem is that most team sports have seasons that span months of competition. Where do you set the peak of training intensity and technical performance? At the beginning of the season? At the middle of the season? The risk of overtraining during the season with an extended period of linearly increasing training intensity is a very real threat for high-level athletes.

Linear periodization is the simplest form of program design, yet it often leaves something to be desired for the athletic population.

Typical Linear Periodization Model

Typical Linear Periodization Model

Block Periodization

Block periodization was introduced by noted sports scientist Yuri Verkhoshansky,[ii] whom we had the opportunity to meet and learn from during our trips to Russia. Professor Verkhoshansky developed his conjugate sequence for Olympic athletes. In no way could our explanation of his work come close to covering the full scope of his methods, but his concepts influenced the designs we would later come to use.

Verkhoshansky’s Standard Model for the Main Adaptation Cycle[iii] Model

W = Work Power Vol = Volume f = Maximal level of functional parameters

His method consisted of a block design of accumulation and restitution. The emphasis of the first block—Block A in the image—was on improving an athlete’s motor potential and morphological and functional specialization. It was largely to build a strength base to facilitate muscular adaptation and an improved work capacity using what Verkhoshansky termed “special physical preparation (SPP) loads.”

As athletes transitioned into Block B, the SPP loads would be gradually replaced by higher intensity training focused on speed and technique. Block B dedicated development to more specific work of the Olympic lifts to accustom the athletes to make full use of their increasing motor potential to execute the lifts.

Finally, Block C used competition training loads to address the maximum level of power and full motor potential of the athletes. This block would cover the most important competitions, so they were performing at their peak output for competition.

The blocks would progress to build a foundation of work capacity and strength, then advance toward power and speed, and ultimately maximal power development.

In a general sense, the design is to overload the volume of strength and power development during an accumulation phase with higher-volume training and maintenance of the athlete’s technical abilities. Then, during a restitution phase, the training volume would be just enough to maintain and gradually progress the strength qualities while training intensity increases and the emphasis is on improved technical proficiency and speed for the sport. That is why each block appears with a gradually increasing, then decreasing line.

Multiple blocks of accumulation and restitution could then be programmed over the course of months to prepare for competition. That basic principle of a wave-like variability in training volume and intensity forms the basis for the undulating model we utilize.

Undulating Periodization

This system makes use of Verkhoshansky’s periodization ideas, with the addition of a more frequent undulating periodization pattern. Within undulating periodization, the volume and intensity of work is constantly varied throughout a planned wave-like pattern.

Undulating periodization aims to maximize the body’s adaptation best seen through the theory of Hans Selye’s General Adaptation Syndrome (GAS).[iv] His work from the 1940s and ’50s explained the way the body responds to stress and works to restore itself to balance, also known as homeostasis.

General Adaptation Syndrome

General Adaptation Syndrome

When a body is exposed to a stimulus, there will be an initial fatigue or strain to a physiologic process. Once the stimulus is removed, the body will recover and adapt to regain a level of balance. The body then begins the process of reinforcing, or super-compensating, to prepare to better handle the stimulus the next time it arises. If the stimulus never recurs, the body returns to the previous baseline. Given a large enough or consistent stimulus, a body will go through successive super-compensations to better handle the stresses, and that baseline level of function will gradually increase.

When a person takes up a strength training program, the body will improve the efficiency and output of the nervous system, reinforce bones and tendons, and grow new muscle fiber to withstand the repeated stress of lifting weights. Too little load, volume or frequency and the body will not need to reinforce itself. Too much load, volume or frequency, the body will be unable to keep pace with the strain and will begin to break down.

The body’s systems will possibly reach a certain point of development at which it can tolerate the stress without an added need for adaptation. This is when most athletes hit a plateau in their progress, and the stressors need to be changed to elicit new development.

As we noted with the linear periodization example, if there is a shift in the training stress away from a hypertrophy focus, a body will gradually lose some of that hypertrophy as it adapts to the new stimulus of a higher intensity and lower volume training.

A body will adapt to the specific demands placed on it. There has been evidence that using an undulating design is superior in developing strength gains and may mitigate the risk of plateaus for well-trained athletes who are more likely to encounter training plateaus compared with less-experienced athletes.[v]

With an undulating program, the training volume and intensity are varied between each workout, week-to-week and month-to-month, making the stress to the body constantly changing.

Variability does not mean random!

There is a planned pattern of change. This method allows for simultaneous work on the primary qualities of hypertrophy, strength, and power without allowing the body to fully adapt to a single stress. As the volume is consistently waved, the risks of overtraining and hitting a prolonged plateau of progress are practically nonexistent, as recovery is built in.

Often, with undulating periodization volume and intensity will move in a reciprocal pattern to one another. When intensity increases, volume decreases, and vice versa. In our experience, an undulating model where the two variables are uncoupled is a somewhat more challenging design, yet one that has proven the most beneficial. Each variable will ebb and flow throughout the training cycle; however, both will be tightly constrained to maximize gains while minimizing the risk of overtraining.

Undulating Progression

Undulating Progression

Some coaches suggest that an undulating progression is not the best method for maximally developing a single quality. That argument has merit; however, there are few sports that require proficiency in a single physical quality.

A football linebacker must have muscle mass to withstand impact, strength to bring down 200-pound running backs, and the power and speed to react and move rapidly to chase receivers. A basketball power forward needs speed and power to sprint and jump, strength to post up and lean on defenders and work capacity to sustain that effort with limited breaks in the action.

Because sports require some expression of almost all of the physical qualities, any significant deficiency in one will ripple outward and negatively impact the others. This is how we end up with a brutally strong football lineman who is too slow to get down the field to block effectively, or the lightning-quick hockey forward who is too weak to fight for position against bigger defenders.

In terms of efficiency, in order to train all of the physical qualities with a reduced risk of overtraining, there is no other method of program design that comes close to an undulating pattern.

[afl_shortcode url=”https://www.otpbooks.com/product/the_system_periodization/?ref=20″ product_id=’47330′]

Tap into the Brains of Some of the World’s Leading Performance Experts

FREE Access to the OTP Vault

Inside the OTP Vault, you’ll find over 20 articles and videos from leading strength coaches, trainers and physical therapists such as Dan John, Gray Cook, Michael Boyle, Stuart McGill and Sue Falsone.

Click here to get FREE access to the On Target Publications vault and receive the latest relevant content to help you and your clients move and perform better.

[i] Verkhoshansky, Y. Special Strength Training: Manual for Coaches. Verkhoshansky SSTM, 2011

[ii] http://www.verkhoshansky.com/Articles/EnglishArticles/tabid/92/Default.aspx

[iii] Verkhoshansky, Yuir. Organization of the Training Process. Translated from Italian

http://www.verkhoshansky.com/Portals/0/Articles/English/Organization%20Training%20Process.pdf Accessed 1/25/2018

[iv] Selye, H. The general adaptation syndrome and the disease of adaptation. Journal of Clinical Endocrinology, 6, 117–231, 1945.

[v] Rhea, MR, et al., “A Comparison of Linear and Daily Undulating Periodized Programs With Equated Volume And Intensity For Strength,” Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research, 2002, 16(2), 250–255.